|

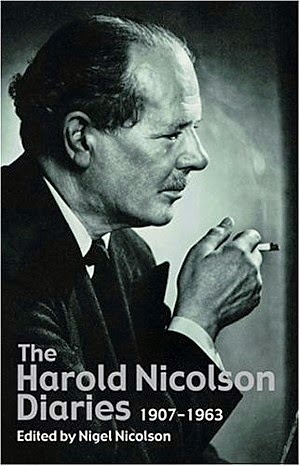

Miller and Monroe in happier days |

... a young woman to whom Kazan had introduced me some days before created a quickened center for the company's interest, attended by its barely suppressed sneer. Her agent and protector, Johnny Hyde, had recently died, but not before managing to get her a few small roles that had led to John Huston's using her in The Asphalt Jungle as Louis Calhern's mistress. In a part practically without lines, she had nevertheless made a definite impact. I had had to think for a moment to recall her in the film. She had seemed more a prop than an actress, a nearly mute satirical comment on Calhern's spurious property and official power, the quintessential dumb blond on the arm of the worldly and corrupt representative of society. In this roomful of actresses and wives of substantial men, all striving to dress and behave with an emphatically ladylike reserve, Marilyn Monroe seemed almost ludicrously provocative, a strange bird in the aviary, if only because her dress was so blatantly tight, declaring rather than insinuating that she had brought her body along and that it was the best one in the room. And she seemed younger and more girlish than when I had first seen her. The female resentment that surrounded her at Feldman's approached the consistency of acrid smoke. An exception was the actress Evelyn Keyes, a Huston ex-wife, who managed to draw Marilyn out, sitting with her on a settee, and who softly said to me later as she watched her dancing with someone, "They'll eat her alive."

... A few days earlier I had gone to the Twentieth Century Fox studio with Kazan. ... We had just arrived on a nightclub set when Marilyn, in a black openwork lace dress, was directed to walk across the floor. ... She was being shot from the rear to set off the swiveling of her hips, a motion fluid enough to seem comic. It was, in fact, her natural walk: her footprints on a beach would be in a straight line, the heel descending exactly before the last toeprint, throwing her pelvis into motion.

... The three of us [Miller, Monroe and Kazan] wondered through a bookstore. ... She had said she liked poetry, and we found some Frost and Whitman and E. E. Cummings. It was odd to watch her reading Cummings to herself, moving her lips - what would she make of poetry that was so simple and yet so sophisticated? I could not place her in any world I knew; like a cork bobbing on the ocean, she could have began her voyage on the other side of the world or a hundred yards down the beach. There was apprehension in her eyes when she began to read, the look of a student afraid to be caught out, but suddenly she laughed in a thoroughly unaffected way at the small surprising turn in the poem about the lame balloon man - "and it's spring!" The naive wonder in her face that she could so easily respond to a stylized work sent a filament of connection out between us.

... She [Marilyn] was a whirling light to me then, all paradox and enticing mystery, street-tough one moment, then lifted by a lyrical and poetic sensitivity that few retain past early adolescence. Sometimes she seemed to see all men as boys, children with immediate needs that it was her place in nature to fulfill, meanwhile her adult self stood aside observing the game. Men were their need, imperious and somehow sacred. She might tel about being held down at a party by two of the guests in a rape attempt from which she said she had escaped, but the truth of the account was far less important than its strange remoteness from her personally. And ultimately something nearly godlike would emerge from this depersonalization. She was at this point incapable of condemning or even of judging people who had damaged her, and to be with her was to be accepted, like moving out into a kind of sanctifying light from a life where suspicion was common sense. She had no common sense, but what she did have was something holier, a long-reaching vision of which she herself was only fitfully aware: humans were all need, all wound. What she wanted most was not to judge but to win recognition from a sentimentally cruel profession, and from men blinded to her humanity by her perfect beauty. She was part queen, part waif, sometimes on her knees before her own body and sometimes despairing because of it - "Oh, there's lots of beautiful girls," she would say to some expression of awed amazement, as though her beauty betrayed her quest for a more enduring acceptance. I was in a swift current, there was no stopping or handhold, she was finally all that was true. What I did not know about her was easy to guess, and I suppose I felt the pain of her memories even more because I did not have her compensating small pride at having survived such a life.

... She knew she could walk into a party, like a grenade and wreck complacent couples with a smile, and she enjoyed this power, but it also brought back the old sinister news that nothing whatsoever could last. And this very power of hers would eat at her one day, but not yet, not now.

... Oddly enough, she seemed not to know fear as she went about rearranging her life; it was when she tried to assert herself and act that the terrors she was born to had to be downed. Strassberg had suggested she study the part of Anna in O'Neill's Anna Christie, and one evening she tried a few pages. Here was the first inkling of her inner life, she could hardly read audibly at first, it was more like praying than acting. "I can't believe I am doing this," she suddenly said, laughing.Her past would not leave her even for private affirmation of her value, and that past was murderous. Something like guilt seemed to suppress her voice.

... Marilyn came up to Boston for the day. No one recognized her in her heavy cable-knit sweater, a deep white knitted hat that came down over her forehead, a black-and-white checked woolen skirt, and moccasins. at twenty-nine she could have been a high school girl. Her sunglasses attracted a few glances on the street since the weather was so dark and overcast. We took a long walk, saw a new movie, Marty, in a neighborhood theatre, and ate in a diner where the waitress, mysteriously drawn to her, kept talking at her, instinctively smelling out something unique about her even in those unexceptional clothes.

A podiatrists' association, she said, wanted to take casts of her feet because they were so perfectly formed, and a dental school wanted one of her mouth and teeth, which were also flawless. Not without fear we sat looking at each other waiting for the future to come closer.

"I keep trying," I said, "to teach myself how to lose you, but I can't learn yet."

Her face filled with an unspoken anxiety. "Why must you lose me?" And she removed her glasses with a compassionate smile.

The waitress, a middle-aged woman with bleached hair, happened to pass out table just then and overheard Marilyn. Her mouth dropped open in recognition, and she turned fully to me with a mixture of amazement and resentment, perhaps even rage, that I would be so stupid or cruel as to cause her idol the slightest unhappiness. In that second her proprietary sheltering of Marilyn, whom she knew only as an image, sprung forth. In a moment she was back with a piece of paper to be autographed.

As we walked back to the hotel, Marilyn sensed an amorphous weight on me. "What is it?"

"It's as though you belong to her." I left out the rest of it.

"It doesn't mean anything."

But on that empty sidewalk we were no longer alone.

... By this time [1956] she had been in psychoanalysis for more than a year.with a woman doctor in New York and there would later be two more analysts, ... both of the physicians of integrity and unquestionably devoted to her. But whatever its fine details, the branching tree of her catastrophe was rooted in her having been condemned from birth - cursed might be a better word - despite all she knew and all she hoped. Experience came toward her in either of two guises, one innocent and the other sinister, she adored children and old people, who, like her, were altogether vulnerable and could not wreck harm. But the rest of humankind was fundamentally dangerous and had to be confounded, disarmed by a giving sexuality that was transfigured into a state beyond even feeling itself, a purely donative femininity. But that too could not sustain forever, for she meant to live at the peak always; only in the permanent rush of a crescendo was there safety, or at least forgetfulness, and when the wave dispersed she would turn cruelly against herself, so worthless, the scum of the earth, and her vileness would not let her sleep, and then the pills began and the little suicides each night. But through it all she could rise to hope like a fish swimming up through black seas to fly at the sun before falling back again. And perhaps those rallies - if one knew the sadness in her - were her glory.

|

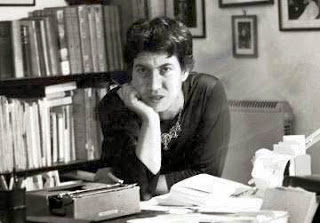

Miller in 1987, the year his autobiography was published. |

To find out more or to order a copy click on the banner below and paste this ISBN No. into the search box > > > 1408836319